The Prince portrait: Lynn Goldsmith vs Andy Warhol

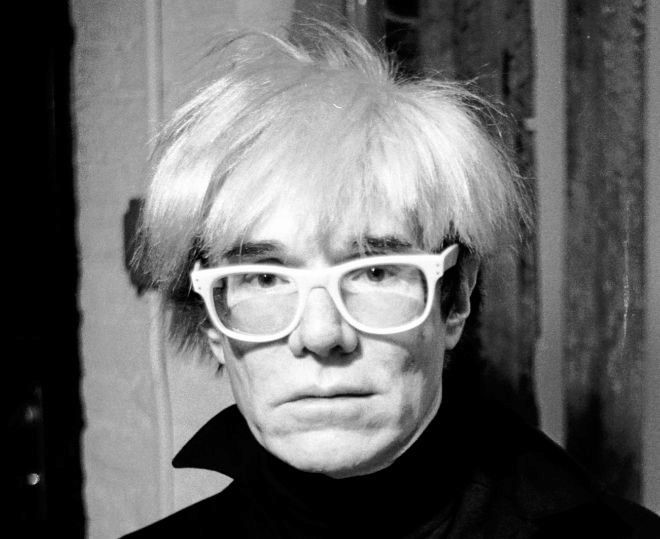

The name Andy Warhol sounds probably familiar to you. He’s the icon of Pop Art, an American artist, film director and producer with crazy wild white hair, known for Campbell’s soup painting and portraits of famous people, such as Marylin Monroe, Liz Taylor, John Lennon, Mao Zedong, Prince and many others.

Lynn Goldsmith sounds probably less familiar. She’s an American recording artist, a film director, a celebrity portrait photographer, and one of the first female rock and roll photographers. Her portraits cover big names of the music scene, like David Bowie, Freddy Mercury, Sting, Rolling Stones, Miles Davis and many others. And Prince.

Screenshot from Lynn Goldsmith’s website

Now, we know that Warhol must have taken somewhere the picture he used for his portraits, but we usually don’t think about it: I mean, we see the transformation he made to the picture, the way he added colors and lines to it, and basically the original photo takes a back seat.

But what if the original picture is well recognizable and taken without the consent of the author? How far does the copyright law protect authors?

Andy Warhol’s portrait of Mao based on an image on the cover of “The little red book”, a collection of quotation from the Communist Chinese leader.

The question is not idle. In the case of Prince portrait, Warhol used a photograph of the famous musician taken by Lynn Goldsmith back in 1981 and licensed to the magazine Vanity Fair.

When Vanity Fair commissioned Goldsmith’s photograph for an article on Prince, the magazine did not inform her that Warhol would be separately commissioned to turn that image into a silkscreen to signal the musician’s iconic Pop status. Goldsmith also did not know that the Pop artist would make 15 works based on that image that would become known as his “Prince Series”. She learned that in 2016, after Prince’s death.

After Prince died in 2016, Condé Nast (Vanity Fair’s parent company) published a Prince tribute magazine that utilized Warhol’s visual work without any credit to Goldsmith. When Goldsmith complained, the Warhol Foundation sued Goldsmith in 2017, to prevent her getting the chance to file a copyright infringement lawsuit first, claiming that she was attempting to “shake down” the organization.

Prince as portraited by Lynn Goldsmith (left) and Andy Warhol (Right)

The Warhol Foundation argued that the paintings were transformative enough to be considered new works and, therefore, to be consistent with the definition of “fair use” under U.S. copyright law.

Goldsmith, on her side, accused the Warhol painting of being an infringement of her photo, and filed a countersuit for copyright infringement.

Andy Warhol. Photo Jill Kennington/ Hulton Archive / Getty

The litigation ended up in a ruling in favor of Warhol Foundation in 2019. As reported by the Associated Press, the judge noted that the “humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone”.

Furthermore, he wrote, each of Warhol’s Prince works “is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince - in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs.”

Goldsmith filed an appeal to what she considers a “gradual erosion of photographers’ rights in favor of famous artists who affix their names to what would otherwise be a derivative work”.

And here we come to the decision of the Second Court of Appeals, given out on March 26, 2021.

The appellate court reversed the first decision and found that the photograph and the Warhol work show that the main purpose and function of the two works are identical: they are created as works of visual art and are portraits of the same person taken at the same time from the same view. And the Warhol work retains the essential elements of Goldsmith’s photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements.

In other words, Warhol’s portrait cannot be considered fair use.

Lynn Goldsmith/Pinterest

But what is “fair use”? In its most general sense, a fair use is any copying of copyrighted material done for a limited and socially beneficial activity, such as criticism, comment, parody, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. Such uses can be done without permission from the copyright owner.

Other important considerations are whether the use is commercial or non-commercial (non-commercial use is more likely to be deemed fair use than commercial use) and whether the use is “transformative”.

Now, the definition of “transformative” in art can lead to a very long, philosophical discussion. For now, we can say that, according to the U.S. Supreme Court, a work is transformative if it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message”.

It should be noted, though, that adding a new aesthetic or new expression to an existing work is not necessarily transformative. There is another type of protected work that incorporates an original work and adds something new: a derivative work. For example, a film adaptation of a novel is a derivative work.

As a matter of fact, Warhol’s works are among many pieces that incorporate, appropriate, or borrow from protected material. Risk of a copyright suit or uncertainty about an artwork’s status can inhibit the creativity that is a goal of copyright.

This is the reason why the “fair use” is much more than simply transformation. The “transformative” nature of a secondary work has become the dominant focus in determining whether that work is protected by fair use; but labeling a use ‘not transformative’ must not be intended as a shorthand for ‘not fair,’ and correlatively ‘transformative’ is not ‘fair’. There are, as mentioned, many other factors that should be considered.

In the specific case, the effect of the Prince Series on the market for Goldsmith’s photograph played an important role.

Andy Warhol’s Prince illustration based on the Lynn Goldsmith photograph as it appeared in Vanity Fair

According to the Second Court of Appeals, in fact, the decision “depends heavily on the commercial competition between the photograph and the reproduced versions of the Prince Series”.

Even though the market for the photograph and the market for the original Prince Series works are distinct, “when represented on a magazine cover, the Prince Series functions as a portrait of the musician Prince – as does Goldsmith’s photograph. The Prince Series retains the photograph’s expressive capacity for Prince portraiture and is sought for that purpose. It may well compete for magazine covers, posters, coffee mugs, and other media featuring the late musician”.

Focusing on the importance of this element is consistent with the fact that fair use is part of the copyright, which is a commercial right, intended to protect the authors, to stimulate author’s creativity by enabling them to earn money from their creations.

So, the Prince Series works are substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph as a matter of law. At least for the moment: the Warhol Foundation already announced its plan to appeal the ruling.